- HOME

- ABOUT ME

- movies

- MEDIA

- L.Onerva

- Eino Leino

- Eeva-Liisa Manner

- Erään Opon päiväkirja

- Elämänkenttäni

- Elämäni ”viiva”

- Käyttöteoriani – se miten minä ohjaan

- Kulttuuritietoinen ja kansainvälistyvä ohjaus

- Ohjauksen järjestäminen maahanmuuttajakoulutuksessa

- Ohjauksen yhteiskunnallinen viitekehys

- Ohjaukäsite

- Oma opiskeluorientaatio

- Opiskelijoiden yksilöllisyys ohjauksessa

- EETTISET KYSYMYKSET

- Psykososiaalisen kehityksen teoria

- Suhteeni erilaisuuteen ja tehtäväni opinto-ohjaajana

- Opinto-ohjauksen ja erityisopetuksen yhtäläisyyksiä ja eroja

- Kehitykseni opinto-ohjaajana

- Maahanmuuttajan uraohjaus

- Maahanmuuttajien ohjaus ja neuvonta: kuka, mitä, miten?

- Ohjauksen tulevaisuus

- Elämänkenttäni

- Mariana Marin

- Claudiu Komartin

- Mariana Codrut

- Roland Erb

- Romanian poetry

- ESSAYS

- STORIES

- CLASSIC POETRY

- CONTEMPORARY POETRY

- TRANSLATED POEMS

- READING POETRY

- CONTACT

- translated Italian-English

- translated Italian-Romanian

- translated Spanish-English

- translated Spanish-Romanian

essays

Ted Hughes to Sylvia Plath

POSTED IN essays May 1, 2012

|

“Last Letter” by Ted Hughes

What happened that night? Your final night.

Double, treble exposure Over everything. Late afternoon, Friday, My last sight of you alive. Burning your letter to me, in the ashtray, With that strange smile. Had I bungled your plan? Had it surprised me sooner than you purposed? Had I rushed it back to you too promptly? One hour later—-you would have been gone Where I could not have traced you. I would have turned from your locked red door That nobody would open Still holding your letter, A thunderbolt that could not earth itself. That would have been electric shock treatment For me. Repeated over and over, all weekend, As often as I read it, or thought of it. That would have remade my brains, and my life. The treatment that you planned needed some time. I cannot imagine How I would have got through that weekend. I cannot imagine. Had you plotted it all? Your note reached me too soon—-that same day, My love-life grabbed it. My numbed love-life Their obsessed in and out. Two women That night That Sunday night she eased her door open Susan and I spent that night What happened that night, inside your hours, At what position of the hands on my watch-face |

||||

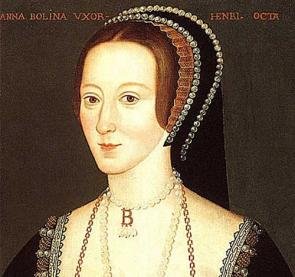

Anne Boleyn

POSTED IN essays April 30, 2012

|

“Good Christian people, I am come hither to die, according to the law, for by the law I am judged to die, and therefore I will speak nothing against it. I come here only to die, and thus to yield myself humbly to the will of the King, my lord. And if, in my life, I did ever offend the King’s Grace, surely with my death I do now atone. I come hither to accuse no man, nor to speak anything of that whereof I am accused, as I know full well that aught I say in my defence doth not appertain to you. I pray and beseech you all, good friends, to pray for the life of the King, my sovereign lord and yours, who is one of the best princes on the face of the earth, who has always treated me so well that better could not be, wherefore I submit to death with good will, humbly asking pardon of all the world. If any person will meddle with my cause, I require them to judge the best. Thus I take my leave of the world, and of you, and I heartily desire you all to pray for me. Oh Lord, have mercy on me! To God I commend my soul.” (Weir 2009, pg. 266 – 267)

Anne Boleyn was the second of Henry’s six wives. She was Queen of England from 1533 until 1536. She was one of the first non-royal women to become a Queen of England, which caused quite a stir in those times. She was also the mother of Elizabeth I, one of the greatest monarchs in the history of England and of the world itself.

Anne Boleyn was in her early to mid-twenties when she attracted King Henry’s attention, in about the year 1525. Her exact age at the time cannot be pinpointed, as the historical records vary as to Anne’s date of birth. It could have been as early as 1500, or as late as 1506. At the time he noticed Anne, Henry had been married to Catherine of Aragon for 16 years.

Anne was a glamorous, exotic young woman of the minor nobility. She had beautiful dark eyes, long black hair, and a slender figure. She was known for her intelligence, lively personality, and keen wit. She was a skilled musician and dancer, and attracted the attention of many men at Court.

Anne’s particular brand of glamour and appeal was different from that of the prevailing standard of female beauty of the times. Light hair, fair and rosy skin, and a womanly figure were among the feminine ideals held in high esteem in Tudor England. The young Catherine of Aragon would have fit this mold perfectly. By contrast, Anne Boleyn was dark, slender and ivory-skinned. She created her own special style by adopting French fashions and customs that she had learned as a lady-in-waiting to Henry’s sister Mary, when Mary was (briefly) the Queen of France.

Henry fell passionately in love with Anne Boleyn, and expected her to become his mistress. Anne refused, which started a chain of events which ended in England’s break with the Roman Catholic Church.

Throughout history, people have wondered how and why Anne held out for so many years before surrendering to Henry. It must have been a challenge, as Henry was King of England, and a very persuasive suitor. Other women had succumbed to his charm and physical attraction. What made Anne behave so differently?

There are several possible explanations. One involves Anne’s love for Henry Percy, a young man she met right around the time King Henry noticed her. Henry Percy was the son of the powerful Duke of Northumberland. Young Percy returned Anne’s affections, and the two planned to marry, provided they could obtain their parents’ permission. Henry Percy was a member of Cardinal Wolsey’s staff, and saw Anne as often as possible when they were both at Court.

When Cardinal Wolsey found out about Anne and Henry Percy’s plans, he refused to let them marry. Lord Northumberland, Percy’s father, also forbade the match, claiming that he had planned to marry his son to the daughter of another high-ranking family. Both Cardinal Wolsey and Lord Northumberland felt that the Boleyns were not prestigious enough to be joined to the Percy family in marriage. It is not certain whether King Henry was behind this, or whether Cardinal Wolsey acted on his own. In any event, the marriage request was denied.

Anne Boleyn and Henry Percy were devastated when they heard the news. Percy was called back home and forced to marry the woman chosen by his family. Anne became bitter and angry, possibly for all her life, that she was denied her true love in marriage. It is not unlikely that she resented King Henry for his role in this, and held it against him for many years.

Another factor in Anne’s refusal to become Henry’s mistress was her sister Mary’s involvement with the King. Anne Boleyn’s older sister Mary had been King Henry’s mistress. Henry ended the affair when Mary became pregnant. Henry arranged for Mary to marry a member of the lesser nobility, and did not acknowledge the child. All in all, Mary did not benefit noticeably from her relationship with Henry VIII. This undoubtedly was a factor in Anne’s decision to withhold her favors from the King.

Henry was determined to divorce Catherine and marry Anne. Catherine refused to give him a divorce, and the Catholic Church would not support Henry’s position. Several frustrating years passed, with Anne clamoring to be Queen, and Henry trying to make it happen.

In 1532, Anne decided she had best become pregnant as soon as possible before Henry lost interest. She was soon was with child, and Henry secretly married her in January of 1533. Shortly thereafter, with the help of Parliament and various advisors, Henry severed ties with the Pope, and declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England. He then divorced Catherine, and forced her to live in exile from Court.

In May of 1533, Anne was crowned Queen of England in a grand, elaborate coronation ceremony. It was supposed to be a festive occasion, but Anne was unpopular with the English people, and their sullenness dampened the event. Many resented Anne for displacing Queen Catherine, who was dearly loved by her subjects. Still in all, Anne’s dream of becoming Queen had come true. She was now the most powerful woman in England.

After achieving their goals, Henry and Anne expected to be happy. Unfortunately, this did not happen. They were both tired and edgy from the stresses of the past several years. In addition, Henry started losing interest in Anne shortly after he fully attained her favors. Henry also finally realized how much his marriage to Anne had cost him. A number of good people, including friends and associates of Henry’s, had lost their lives due to loyalty and treason issues stemming from the English church’s break from Rome.

There was still a son for Henry to look forward to. Henry fully expected Anne to deliver a Prince as she had always promised. In the fall of 1533, Anne’s long-awaited child was born. To Henry’s disappointment, it was a girl. No one knew then that the Princess Elizabeth would turn out to be one of the greatest English monarchs of all time.

Anne had several more miscarriages after Elizabeth’s birth. She and Henry quarreled more, and Anne’s sharp temper took hold, especially when Henry became interested in other woman. After less than three years of marriage to Anne, Henry fell in love with a young gentlewoman named Jane Seymour. Jane Seymour was very different from Anne Boleyn. Unlike the dazzling, dramatic Anne, Jane was gentle, placid, quiet, and very pale. Henry saw her as a source of peace and comfort, and a refuge from life with the turbulent Anne.

After a final unsuccessful pregnancy, Henry decided he had had enough of Anne. He decided to replace her with Jane Seymour. Because Henry would lose face if he divorced Anne after all he went through to marry her, his advisors conspired some false adultery charges against her. To make the charges look outrageous, Anne was accused of adultery with five different men, including her own brother George. George’s wife, the Lady Rochford, testified that her husband had been in intimate contact with Anne. George and Jane’s marriage had been arranged, and was not a happy union. Jane Rochford hated both her husband and her sister-in-law, and envied their family closeness. Lady Rochford’s words, although lies, carried a lot of weight.

Although Anne was truly innocent of all charges, she was found guilty of treason by a court of English statesmen who feared the King. Her own father and uncle voted to condemn her. Because treason was a capital crime, Anne was sentenced to death, and executed in May of 1536. Many were outraged at this miscarriage of justice, even those who had disliked Anne Boleyn in the beginning. As usual, Henry’s advisors were blamed, and Henry kept his popularity among his English subjects. A few weeks after Anne’s death, Henry married Jane Seymour in a quiet ceremony.

Anne Boleyn is remembered for her brilliance, glamour, elegance, and for the incredible hold she held on King Henry for such a long time. Many do not realize that Anne Boleyn was the mother of Elizabeth I, who inherited Anne’s facial features and various facets of her personality. Anne would have been very proud of her daughter. ( Alison Weir)

|

||||

King Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn

POSTED IN essays April 30, 2012

|

These famous love letters from King Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn are undated. They were found in the Vatican Library, possibly stolen from Anne and sent to the papacy during Henry VIII’s struggle for an annulment of his marriage to Katharine of Aragon. Though Henry argued for an annulment on the basis of his conscience (he stated that the marriage was in direct contradiction to the Bible), most people believed he simply wanted to marry Anne Boleyn.

Anne’s replies to these letters are lost.

The letters were written in French.

My mistress and friend: I and my heart put ourselves in your hands, begging you to have them suitors for your good favour, and that your affection for them should not grow less through absence. For it would be a great pity to increase their sorrow since absence does it sufficiently, and more than ever I could have thought possible reminding us of a point in astronomy, which is, that the longer the days are the farther off is the sun, and yet the more fierce. So it is with our love, for by absence we are parted, yet nevertheless it keeps its fervour, at least on my side, and I hope on yours also: assuring you that on my side the ennui of absence is already too much for me: and when I think of the increase of what I must needs suffer it would be well nigh unbearable for me were it not for the firm hope I have and as I cannot be with you in person, I am sending you the nearest possible thing to that, namely, my picture set in a bracelet, with the whole device which you already know. Wishing myself in their place when it shall please you. This by the hand of

Your loyal servant and friend

H. Rex

No more to you at this present mine own darling for lack of time but that I would you were in my arms or I in yours for I think it long since I kissed you. Written after the killing of an hart at a xj. of the clock minding with God’s grace tomorrow mightily timely to kill another: by the hand of him which I trust shortly shall be yours. Mine own sweetheart, these shall be to advertise you of the great loneliness that I find here since your departing, for I ensure you methinketh the time longer since your departing now last than I was wont to do a whole fortnight: I think your kindness and my fervents of love causeth it, for otherwise I would not have thought it possible that for so little a while it should have grieved me, but now that I am coming toward you methinketh my pains been half released…. Wishing myself (specially an evening) in my sweetheart’s arms, whose pretty dukkys I trust shortly to kiss. Written with the hand of him that was, is, and shall be yours by his will. |

||||

Catherine of Aragon to Henry VIII

POSTED IN essays April 30, 2012

| The Queen of England and mother to Queen Mary, Catherine of Aragon (1485 – 1536) is best known as the first of the many wives of Henry VIII. Though he divorced her in 1533, Catherine remained devoted to Henry until her death in 1536, as this letter shows.

1535 My Lord and Dear Husband, I commend me unto you. The hour of my death draweth fast on, and my case being such, the tender love I owe you forceth me, with a few words, to put you in remembrance of the health and safeguard of your soul, which you ought to prefer before all worldly matters, and before the care and tendering of your own body, for the which you have cast me into many miseries and yourself into many cares. For my part I do pardon you all, yea, I do wish and devoutly pray God that He will also pardon you. For the rest I commend unto you Mary, our daughter, beseeching you to be a good father unto her, as I heretofore desired. I entreat you also, on behalf of my maids, to give them marriage-portions, which is not much, they being but three. For all my other servants, I solicit a year’s pay more than their due, lest they should be unprovided for. Lastly, do I vow, that mine eyes desire you above all things. |

||||

Ludwig van Beethoven

POSTED IN essays April 30, 2012

| IMMORTAL BELOVED

The First Letter The Second Letter |

||||

Heloise and Abelard

POSTED IN essays April 30, 2012

|

To Peter Abelard:

I have your picture in my room. I never pass by it without stopping to look at it; and yet when you were present with me, I scare ever cast my eyes upon it. If a picture which is but a mute representation of an object can give such pleasure, what cannot letters inspire? They have souls, they can speak, they have in them all that force which expresses the transport of the heart; they have all the fire of our passions…. Heloise ( Heloise was a French nun and was writing to Peter Abelard, a philosopher. Abelard had been her tutor and they were secretly married. They were separated and Abelard was mutilated by order of her uncle. Heloise lived c 1098-1164 ) |

||||

Sibilla Aleramo and Dino Campana

POSTED IN essays April 30, 2012

|

Chiudo il tuo libro,

snodo le mie trecce,

o cuor selvaggio,

musico cuore…

con la tua vita intera

sei nei miei canti

come un addio a me.

Smarrivamo gli occhi negli stessi cieli,

meravigliati e violenti con stesso ritmo andavamo,

liberi singhiozzando, senza mai vederci,

né mai saperci, con notturni occhi.

Or nei tuoi canti

la tua vita intera

è come un addio a me.

Cuor selvaggio,

musico cuore,

chiudo il tuo libro,

le mie trecce snodo.

Sibilla Aleramo a Dino Campana, Mugello, 25-7-1916 |

||||

|

In un momento Sono sfiorite le rose I petali caduti Perché io non potevo dimenticare le rose Le cercavamo insieme Abbiamo trovato delle rose Erano le sue rose erano le mie rose Questo viaggio chiamavamo amore Col nostro sangue e colle nostre lagrime facevamo le rose Che brillavano un momento al sole del mattino Le abbiamo sfiorite sotto il sole tra i rovi Le rose che non erano le nostre rose Le mie rose le sue rose. Dino Campana a Sibilla Aleramo, 1917 |

||||

FAMOUS LOVE LETTERS

POSTED IN essays April 30, 2012

|

Rakkaimpani maan päällä, olen tänään ikävöinyt sinua niin, että olen ollut vähällä kuolla tai tulla luoksesi. Molemmat kiusaukset olen nyt voittanut , en kyllä ilman tuntuvia tappioita. Sinä et ymmärrä, mitä on ikävöidä ja rakastaa niin, että järki meneeja elämä ja kuolema on samantekevää. Niin rakastan minä sinua. Soitin tänään kotiisi, sekä Aristoon ja Espilään. Et ollut missään niistä. Olin nim. aamulla tulla hulluksi rakkaudesta sinuun. Sain panna kaiken tahdon ja älyn voimani liikkeelle ollakseni tulematta nyt yöjunalla luoksesi. Helsinki, 12.03.1915 ( L. Onerva wrote to her husband, the composer Leevi Madetoja)

Älä mitään kysy Älä lemmestä haasta – se pelottaa mua Kaikki ruusut peittää

L. Onerva 12.11.1912 |

||||

The Lover tells of the Rose in his heart

POSTED IN essays April 28, 2012

|

All things uncomely and broken, all things worn out and old, The wrong of unshapely things is a wrong too great to be told; by William Butler Yeats |

||||

Copyright © 2023 by Magdalena Biela. All rights reserved.